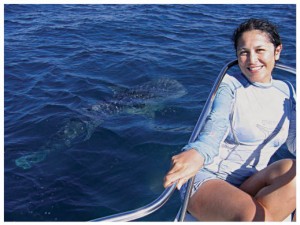

by Sergio and Bryan Jáuregui, photos by Dení Ramírez

If you sift back through the catalog of parental admonitions that were meant to ensure you a long and happy life—you know, “don’t stick your tongue on frozen metal,” “don’t eat yellow snow,” “don’t drink your father’s last bottle of beer”—somewhere buried in there your mother must surely have added “and, oh yes dear, don’t swim with sharks.”

Very sound advice to be sure, but swimming with sharks, whale sharks that is, in the Sea of Cortes is truly one of life’s great (and, sadly for you danger junkies, very safe) adventures. While whale sharks have thousands of teeth in hundreds of rows in their enormous mouths—imagine armed shark mouths 4 to 5 feet wide—they can neither bite nor chew. That’s right, they are happy to forego all human body parts in favor of plankton, krill and small fish. Go figure!

So now you feel safe, but even if you were on the varsity swim team you’re probably wondering how you could actually keep pace with a shark in the water. Well, the whale shark got its moniker because it is the only fish that is literally as big as a whale; mature adults can reach 60 feet in length and 50 tons in weight. Reaching these proportions requires an immense amount of energy, which the whale shark gets by consuming huge volumes of plankton-rich water, then straining it out through its gills. In fact, to get the food it needs it is not unusual for a whale shark to filter 400,000 gallons of water an hour. To conserve this hard-won strength and continue eating, whale sharks tend to do a lot of hanging about in the water, or, if moving, doing so at a very slow pace. This lollygagging is what makes it possible for non-bait types like humans to jump in and swim alongside them for a bit. Of course, when they want to put on the speed they certainly can so when a whale shark tires of your company all you will see is a swishing tail receding into the distance.

Now you’d think it’d be a relatively simple matter to learn about a mammoth fish the size of a school bus dawdling through the waters eating up everything in its path. But the fact is that scientists still know relatively little about the whale shark, and La Paz resident Dení Ramirez of Whale Shark Mexico is trying to change all that. Originally from Mexico City, Dení has been studying whale sharks in La Paz since 2001, and completed her Ph.D. in marine biology last year. The whale shark’s skin is covered in a pattern of pale yellow spots and stripes that is unique to each animal, a type of fingerprint if you will, so Dení has been able to track some of the inhabitants of La Paz Bay. She has been tracking the young sharks Flavio, Tikki Tikki and Tango for almost a decade now, and has determined that they are true Baja residents. While whale sharks have been spotted across the globe from Australia to Djibouti, from the Philippines to Mozambique, Dení’s juveniles appear to travel only in the Sea of Cortés, from the Bay of La Paz to Bahía de Los Angeles, roughly 600 miles. We asked Dení why we seem to be seeing the whale sharks around La Paz so much more over the last couple of years than we ever did before.

“It’s really just a question of food. Over the last two to three years the conditions in the Bay of La Paz have been just right to produce an enormous amount of plankton for the whale sharks to feed on. The wind, currents, mangrove conditions all have combined to create an excellent environment for plankton growth that we just didn’t have for such extended periods in earlier years. Also, in the Bay of La Paz the plankton is rich in coastal waters, and these relatively shallow waters give the young sharks in my group a certain amount of protection.” Dení is happy to take visitors with her on her research trips and share some of her extensive knowledge of whale sharks and research methodology.

Dení is currently doing a lot of work with the pregnant females who inhabit the deeper waters around Espiritu Santo Island and has found that they have much larger migrations than the young sharks due to their different needs as mothers, mothers who surely will work to ensure the long life and happiness of their offspring by admonishing “and dear, don’t try to eat the humans. They’ll just clog up your gills.”

Adventures to swim with whale sharks and sea lions in the Sea of Cortés arranged by request. For more information visit: Todos Santos Eco Adventures at www.TOSEA.net